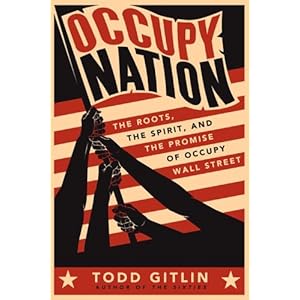

Book Review: Celebrating Occupy’s ‘Demandlessness’

If Todd Gitlin finds it hard to root for a movement that can’t be bothered to advance its own agenda, he doesn’t let on.

Gitlin, a seasoned lefty activist, attempts a biography of the

The e-book is broken into three parts in which Gitlin explores the roots, spirit, and future of the Occupy Wall Street movement respectively. Gitlin is unabashed his admiration for Occupy and its purpose (or lack thereof), despite the most obvious flaws of the movement (which some might argue are exactly its strengths).

Occupy Wall Street did not arise from one source, according to Gitlin, but rather was a convergence of many different movements and responses to Wall Street “insiders who master the game of heads-we-win-tails-we-win-too,” and the government’s failure to promote economic equality – especially what many Occupiers saw as the broken promises of a hopeful Obama administration.

Once Occupy did organize (if that’s the word for it), the movement frustrated politicians and media alike. Though the mainstream media was quick to jump on board with support, the lack of official leaders and an official mission made explaining Occupy to audiences a difficult task. But Gitlin echoes the attitude of the Occupiers, asserting, “It ought to have been obvious what the movement stood for.” As for leadership, or the lack thereof, Gitlin explains it away as semantics. “Leadership is not abolished when movements don’t designate spokespersons and leaders refuse the label, any more than prisons are abolished when they are designated as correctional facilities.”

Instead of designating leaders per se, Occupiers has a system of meetings and hand signals (the “up-twinkles” and “down-twinkles” that have provided comedy gold for conservative observers), all which Gitlin explains and none of which yield a call for actual action, a feeling embraced by OWS: “The encampments were consistently unwilling to make the effort to coalesce around what would conventionally be called demands and programs. Instead, what they seemed to relish most was themselves: their community and espirit, their direct democracy, the joy of becoming transformed into a movement, a presence, a phenomenon that was known to strangers, and discovering with delight just how much energy they had liberated. For indeed, in a matter of days their sparks had ignited a fire.”

And Gitlin’s not referring to the campfires that the occupiers huddle around in Zucotti park. He is referring to the anarchist spirit that drives the occupiers and causes an ideological double standard: “The Occupy movement wanted to win reforms and to stay out of politics. At the same time.” Though Gitlin does note this contradiction, he doesn’t seem bothered by its philosophical impossibility. He notes, “They want to will an end (more equality) while refusing to will the means (reform via government action). Partisans of equality – at least the idea of greater equality are loath to risk surrendering freedom, which to them means freedom from government.”

The irony here is rich. OWS calls for (as much as a movement without demands can call for something) the reissuing of governmental regulations and increased government spending to spread economic equality. Occupy favors the repeal of the Glass Steagall Act, demands more restrictive financial sector regulation than even Dodd-Frank, and its members state repeatedly that government should provide higher education for “free.”

But these are the people Gitlin celebrates for proving, “you do not need institutions because the people, properly assembled, properly deliberating, even in one square block of lower

A movement made up of people who spend so much time ostentatiously relishing themselves, and whose entire existence is mostly empty theater, isn’t much of a threat to the status quo. And according to Gitlin, there is a rift within OWS about how to go about a achieving their unstated goals. Most feel that to work within the “broken” political system they abhor in order to bring about change to it is to offer legitimacy to an illegitimate process.

Gitlin believes that it may be up to those outside the OWS movement to fix the system: “If it’s up to the radicals, among others, to make the Occupy movement endure so that the respectables are forced to take the need for substantive reform more seriously, isn’t it up to the respectables to prove the radicals wrong about whether the American political system can reverse decades of growing inequality?”

As might be expected of an author that coos about OWS’s ability to “regulate themselves,” Gitlin takes care to distance the overall movement from the instances of extreme violence and vandalism, and mainly blames law enforcement for such episodes. He also takes care to accentuate the split between those occupiers who denounce violence as a legitimate avenue of demonstration and those who find it hurtful to the cause but not necessarily illegitimate.

To readers trying to determine what Occupy Wall Street was, or is, all about, “Occupy Nation” offers an inside perspective. But do not expect any answers to the question “What exactly do they want?” because, “Demands conferred legitimacy on the authorities. Demandlessness, in other words, was the movement’s culture, its identity.”