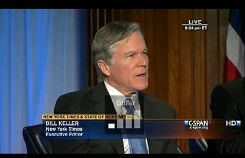

Executive Editor Keller Contemplates Being 'Frog-Marched' in Shackles Over Publishing State Secrets

Secret-publishing editor Bill Keller and conservative critic Gabriel Schoenfeld have a surprisingly amicable discussion on where to draw the line on publishing state secrets in the Internet age.

Published: 4/4/2011 2:10 PM ET

For "Secrecy in Shreds," his latest column for the Times' Sunday magazine, Executive Editor Bill Keller conducted a surprisingly affable conversation with conservative journalist Gabriel Schoenfeld of Commentary magazine, who last year published "Necessary Secrets," a book highly critical of Keller and the Times revealing details of and thus wrecking two successful terrorist-fighting programs - the National Security Agency's secret eavesdropping,, and SWIFT, a Treasury Department program that screened international banking records for suspicious activity.

Regarding Keller's "eavesdropping on Americans without warrants" formula; as Times Watch has pointed out again and again, the N.S.A. spy program monitored international communications from suspected terrorists in America who aren't necessarily U.S. citizens. It's an important distinction, one the Times invariably failed to note, perhaps in order to make the program sound more like an invasion of privacy than it truly was.

Keller confessed to some slight discomfort with the state of leaking of state secrets in the Internet age, which the Times has been in the forefront of, first with the two anti-terror programs and then the publishing of secret diplomatic cables from WikiLeaks.

Keller and Schoenfeld agree that Times editors should not have gone to jail over the leaking of anti-terrorist program details; Schoenfeld would have called for a prosecution and a symbolic fine. Schoenfeld got in a crack at the Times' expense:

Last year, Gabriel Schoenfeld, a veteran of the conservative magazine Commentary, published a book that explained how The New York Times could be prosecuted under the Espionage Act. The book said a lot of other things too, but you'll understand why that particular proposition stuck in my mind. At one point Schoenfeld conjured an image of authorities "frog-marching a shackled Bill Keller into court."

Schoenfeld's book, "Necessary Secrets," is a valuable history-with-attitude of the long war between the American government and the press over the protection and disclosure of secrets. Two stories this newspaper broke were particularly troublesome to him: one, in 2005, about the National Security Agency's antiterror-agents' eavesdropping on Americans without warrants; the other, published in 2006, about the Treasury Department's screening international banking records. Recently I invited Schoenfeld in for a conversation about secrecy, a subject blown back to life by the phenomenon of WikiLeaks.

Regarding Keller's "eavesdropping on Americans without warrants" formula; as Times Watch has pointed out again and again, the N.S.A. spy program monitored international communications from suspected terrorists in America who aren't necessarily U.S. citizens. It's an important distinction, one the Times invariably failed to note, perhaps in order to make the program sound more like an invasion of privacy than it truly was.

Keller confessed to some slight discomfort with the state of leaking of state secrets in the Internet age, which the Times has been in the forefront of, first with the two anti-terror programs and then the publishing of secret diplomatic cables from WikiLeaks.

The digital age has changed the dynamics of disobedience in at least one respect. It used to be that someone who wanted to cheat on his vow of secrecy had to work at it. Daniel Ellsberg tried for a year to make the Pentagon Papers public. There was a lot of time to have second thoughts or to get caught. It is now at least theoretically possible for a whistle-blower or a traitor to act almost immediately and anonymously. Click on a Web site, upload a file, go home and wait.

Keller and Schoenfeld agree that Times editors should not have gone to jail over the leaking of anti-terrorist program details; Schoenfeld would have called for a prosecution and a symbolic fine. Schoenfeld got in a crack at the Times' expense:

"I'm against reform," he told me, referring to the new leak-punishing proposals. "The system has been working reasonably well, with a couple of egregious exceptions - most of them involving The New York Times."